Performance/Installation

Golrokh Nafisi, Ahmadali Kadivar

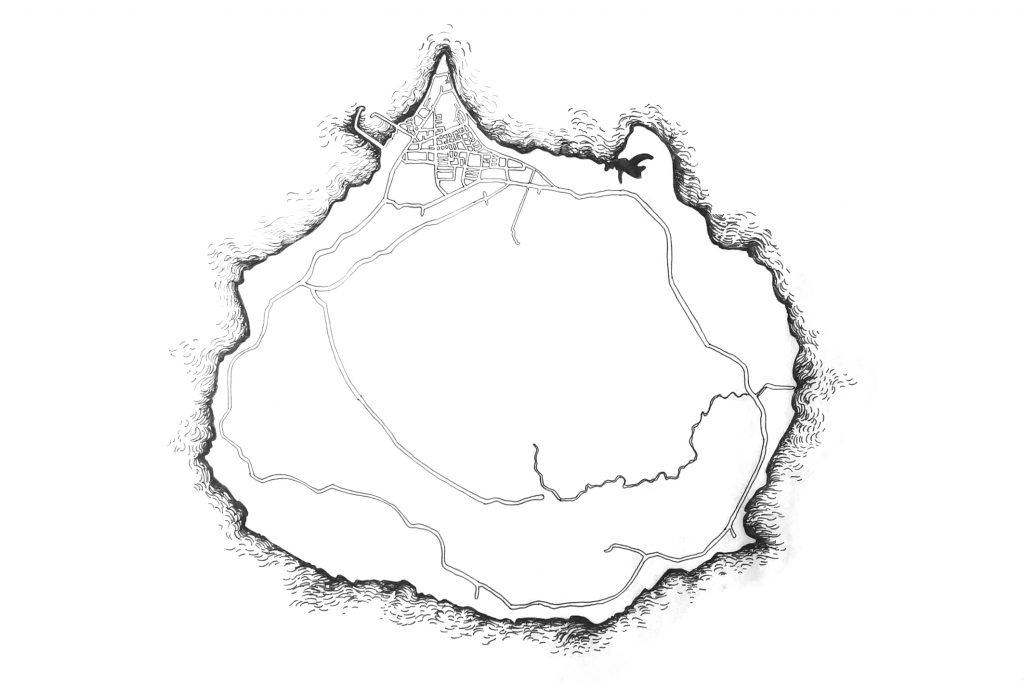

50 handmade maps (90x100cm each)

Participatory performance and installation

Curated by Morteza Niknahad, (1360 foundation)

At Abandoned power plant of Hormoz (Factory 52/72)

Description:

Hormoz is a small island situated in the Persian Gulf, at the Strait of Hormuz. The project “Center the Border” was conceived during the spring of 1398, after the invitation by 1360 Foundation and Bandar Abbas’ artist and curator Morteza Niknaṇad.

The relationship between the island and its inhabitants, living in the island’s only town Hormuz, has similar connotations as other stories of island life. This layered relationship entails an enclosed interaction that goes from proximity to nature—and fishing and swimming at its various beaches on one hand—to fear of unknown linked to marginal places where residents are forbidden to go. Center the Border is an attempt to visualize and locate the relationship that the inhabitants of Hormuz have with their land.

The work is activated by fabric maps prepared beforehand, that are used as active props to interact with the encountered people in order to construct a series of collaborative maps representing Hormoz in relation to its inhabitants’ stories. This was achieved through meetings and conversations, that took place in people’s houses and around this large map—meant to serve as some sort of interactive table cloth. While questions were answered about the places people were scared of or amazed by, and so on, a parallel description of the island’s geography based on people understanding was shaped. This was made visible by the juxtaposition of transparent colorful fabrics on the specific spots on the map where the narration was taking place. In this encounter with the empty map, the inhabitants of Hormuz could view the entire island as one whole and feel the reciprocal sense of belonging, even if for a short time. They could for once see their island as a whole belonging to them, to their history and the history of their family, also gathered around the map.

From the earliest encounter with their words, the questions drafted in advance changed, as words were replaced by the local jargon. Even the names of places as mentioned on google maps and used on tourist guides, were new forms of naming imposed from elsewhere or by tourists’ language. While original names reflected an ongoing and dynamic relationship between the inhabitants and the place, the “new names” belonged to outsiders. One beach, for example, was locally known as Kalsaghoon, in reference to “a dog biting your robe as you walk,” due to the sharp rocks along the beach where fishermen would get stuck on as they landed their boats. Instead the new name “One Tree Beach” was reflecting the view of an outsider seeing the landscape for the first time, through a “touristic” frame. The outsiders’ names, however, have become the “official” names used in Google Maps and elsewhere.

The collective life inside Hormuz’s houses transformed each one-on-one map conversation into a collective conversation in which those involved invoked family, friends, and neighbors, who then often entered the conversations themselves. Individual memories met each other in the same places, and the lives of neighbors and relatives collided on the colored spots applied on the maps. These color spots indicate places where these people were hanging out during their childhood, or their favorite place for fishing, or even the places related to sentiments such as fear, or prohibited routes of the island.

These conversations also uncovered people’s relationships to the island’s spiritual beings, from jinn—crafty spirits that wander on dark edges—to baad—ghosts that travel with the wind that are of East African origin—and other otherworldly creatures that inhabit Hormuz and are embedded in its landscape. One of the most frequently mentioned was The Father of the Sea, a ghostly old man with long hair who could be seen in the late evenings walking above the surf in the distance. These spiritual beings, understood and seen with a mix of caution and respect by locals, reflected an inheritance passed along over many generations.

In the end, the result was installed at the abandoned power plant of Hormoz, which was opened several months ago in conjoined effort by the artists of Hormuz and Bandar Abbas, after twenty years of silence and inactivity. The colored and empty maps resulted in an installation of a “map workshop.” The workshop continued inside the chamber of the three-wheel motorbike, which is the main transportation mean in the island of Hormuz. Visitors could sit back and answer the same set of questions posed to the people that previously opened the doors of their house.

Statement:

Maps are drawn from a perpendicular view of the earth. The one who has the privilege to look vertically and draw the maps dominates people who are not able to look from above: colonial history is tangent to the history of drawing maps. Newcomers draw plans and maps as means to control the “new” lands. In order to break this domination, this vertical view must be turned into a collective view (the focal point of the mapping has to be transformed into a diverse collective view). Looking down from above together, and imagining quality rather than focusing on conventional measurements; a quality that is deeply connected to collective memories, historical events, myths and beliefs of people who actually shape the maps on Earth. The map, so often a colonial tool of domination, was converted into a toll for collaborative imagining.

Abandoned places are not desolate spaces, on the contrary, they have accumulated all the facilities and the potential that they can turn into. The electric power plant in the Hormoz Island has been abandoned for twenty years now, after twelve years of mass production of electricity for the people of Hormuz. In the first week of May 2019, this accumulation of opportunities was turned into a workshop for drawing collective maps of Hormuz based on qualitative elements. This represents probably only a couple of seconds in the long life span of centuries of the island’s history, just a few fleeting moments of production that followed the silence of the power plant.

When seven hundred years ago, the famous Moroccan traveler and writer, Ibn Battuta (ابن بطوطه) wrote a number of pages on his itinerary describing the booming Hormuz Bazar, he mentioned the diverse people from Rome and African countries and India as well as the unique sense of humor of its Sultan. Ibn Battuta was undoubtedly not the first nor the last surprising traveler on the island of Hormuz, and in the up-and-coming history of the island, those who later came to a surprise from the location of the island did not occasionally write only an itinerary, but also developed the will to seize the island and occupy it. From Alfonso Dalbokker, the Portuguese colonist, who arrived to Hormuz two hundred years after Ibn Battuta, and colonized Hormuz Island for one hundred and thirty years for the Portuguese empire, to Imam Gholi Khan, the Persian ruler who surrounded and then conquered the island for Shah Abbas, And he stepped in to it for the first time, to Mo’in al-Tojar Bushehri, which allowed him to extract the red soil of Hormuz during the Qajar period and early on in the first Pahlavi, all imagined themselves as Narrator, Conqueror and Discoverer of Hormuz.

How is it that this island, present in most of the world’s itineraries, historiography, and the drawing of ancient maps, such as the “The sea of Pars” map (from Masalek and Mamalek book), in the eyes of the newcomers, is still imagined as a new world and a discovery? Is the island as surprising as the newcomers are to Hormuz, just as newcomers see the island as a “discovery” after the first encounter with Hormoz? Or is it Hormuz, laced on the North of the strait of the same name, that for centuries has been witnessing the arrival of newcomers, generously enabling them to be the first explorers of its subtle nature?

Environmental warnings claim that Hormoz is in danger. Thinking of looting a land in the name of human being is not merely the task of environmental activists, it is a prerequisite for our presence in different times and places. A window from where the world should be look at, again, from anew. The island of Hormuz is ecologically young. The reason of the seven colors of the sands that characterize the island, carry also the youth and the fragile texture of the island. This geologically young island now sees the arrival and departure of thousands of tourists every day. Walking in such territory, in the days when island tourism increases everyday, the question should be what is “our” responsibility towards this land and its unique nature?

Hormuz is also a border, and borders can be turned into terrified souls full of fears from the invasion of foreigners or, in an incredible position, the source of the inspiration of the people in the center, in relation to the world around them. Throughout history, Hormoz was an island that brought Gulf people to India, Europe and Africa, and during its boom it has been a meeting place for people from all over the world. Today, the people of Hormuz have opened doors to their visitors in the same way. But does this openness make the island more abundant or endangered? Will the dream of progress with the promise of prosperity, along with high-speed cars, roads, hotels and high buildings also swallow the island of Hormuz? Or are those who have seen Hormuz as a source of inspiration for their works over the past years as well as the local forces committed to nature capable of resisting this single image of development? What exactly is this resistance against?

When center-dwellers move to the frontiers, whether they come from other continents or from our own capital, they speak of the need for “education” and “educating” the locals as insurance against any accusation that might be lobbied against them. The “center” often consider himself as an educator and as the carrier of civilization to the land he discovers. The assumption of this position is, of course, the result of a vacuum of geographic and historic knowledge in the minds of the residents of the capital about the places they seek to “explore” and “discover.” Therefore, it is necessary to obsessively observe this behavior in order to threaten the dominant position of the center-dwellers who have gone to the borders. This can be done by understanding the history and geography of the island. Borders are the starting point for thinking about our collective life. The island of Hormuz is the center of the history, in its ups and downs.

Is it possible to take responsibility without restoring history to the present and to get a deeper understanding of the soil and ground that we are thriving for? The restoration of history to the moment is not intended to justify or romanticize the glorious times in the past, but to return to the roots that make the main changes possible in order to recognize the soil. We must recognize the soil not only in its beautiful colors, but also in the fact that we all share in its consumption.

March 2019

Golrokh Nafisi,

Ahmadali Kadivar

May 2019